Standards, right?

Standards have been around since way before the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) and the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). Standards are a reality for classroom teachers and personally, for me, I can teach using Standards as guidelines. I trust that people smarter than me chose the standards, taking into account what kids need to know to be successful that is developmentally appropriate. How we use standards determine how well our students learn and whether or not we are preparing for life in the 21st century. It’s up to us, the professionals, to use the standards in the best ways to support our students. Since standards are the reality of our work, let’s share ways to best use them to support our young learners!

CCSS-ELA in Particular

The CCSS for English/Language Arts (ELA) were developed with three shifts for teachers to make in their teaching. I’ve attended three trainings on these shifts, coming at it from the point of view of a Science teacher, and each time I learn more about the three shifts. Even though I teach Science and am working on aligning the way I teach to the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), I also have my students read and write so I’ve been familiarizing myself with the CCSS-ELA. Looking back at my notes I want to remember to explain to my students that these shifts, or literacy, is like breathing. We need to breathe in and out to survive. In literacy breathing in, or taking in, is done by reading and listening. Breathing out is done by writing, presenting and speaking. I like that analogy. The three shifts called for in the CCSS-ELA are as follows:

- Regular practice with complex text and its academic language.

- Reading, writing and speaking grounded in evidence from text, both literary and informational.

- Building knowledge through content-rich nonfiction.

This post will focus on the first shift; I will share what I’ve learned about shifts 2 and 3 in future posts.

Complexity

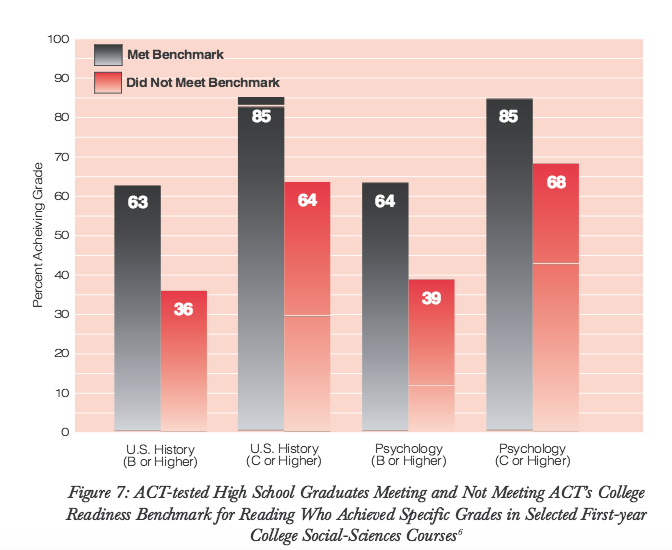

Why is text complexity so important in preparing our kids for their futures? To show us the importance of text complexity to future success, we were shown some data from the 2006 ACT report, Reading Between the Lines, What ACT Reveals about College Readiness in Reading. They found evidence that reading affects how students do in other subjects that have complex texts. Figure 7 from the ACT report shows that students who met the ACT benchmark, what they consider “college-ready,” did better in their US History and Psychology class. Looking at students who scored a C or better and a B or better, in both cases more of the students who met the ACT benchmark scored better in both US History and Psychology.

What About Reading Sets Them Apart?

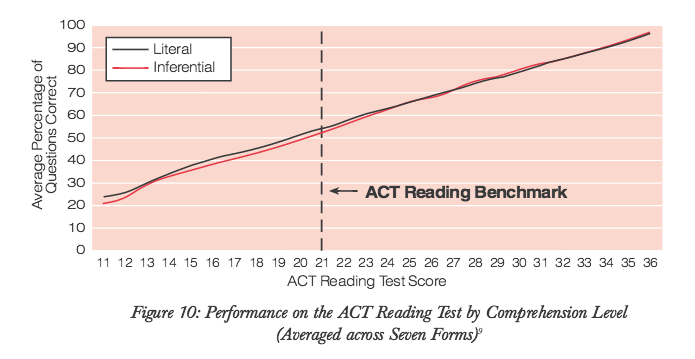

So they decided to look at specifically what differentiated the students who met the ACT reading benchmark versus those who did not meet the benchmark. They looked at inferential comprehension and informational comprehension to see if that’s what separated those who met benchmark, and also had more success in other classes where they had to read complex texts, and those didn’t meet the reading benchmark, and didn’t do so well in their other classes. As the graph in Figure 10 shows, students who can read literally, can read inferentially. As the ACT reading test score rose, so did the average percentage of questions correct for both inferential AND literal comprehension. The red and blue lines rise almost identically. Okay, no luck there.

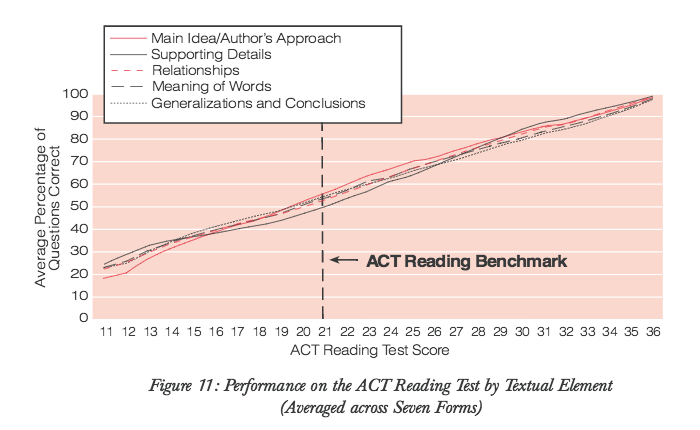

So if reading literally or inferentially improves as student reading ability improves then what will help our students improve their reading ability? They also looked at textual elements, specifically reading strategies, main idea/author’s approach, supporting details, relationships, meaning of words, and generalizations and conclusions. The graph on Figure 11 shows a similar finding as the comprehension finding! As ACT reading scores improved, the average percentage of questions correct improved equally across all the reading strategies. So focusing on teaching our kids those reading strategies doesn’t lead to any more improvement than any strategy on its own.

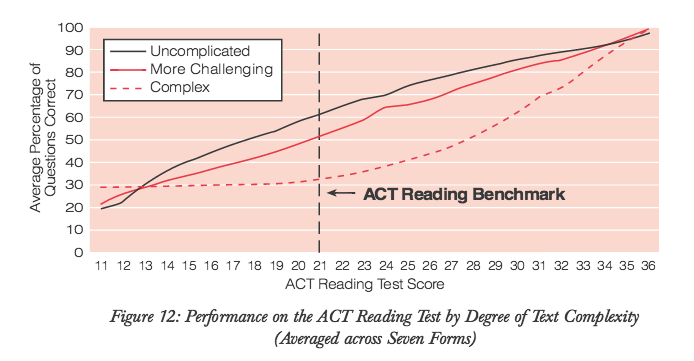

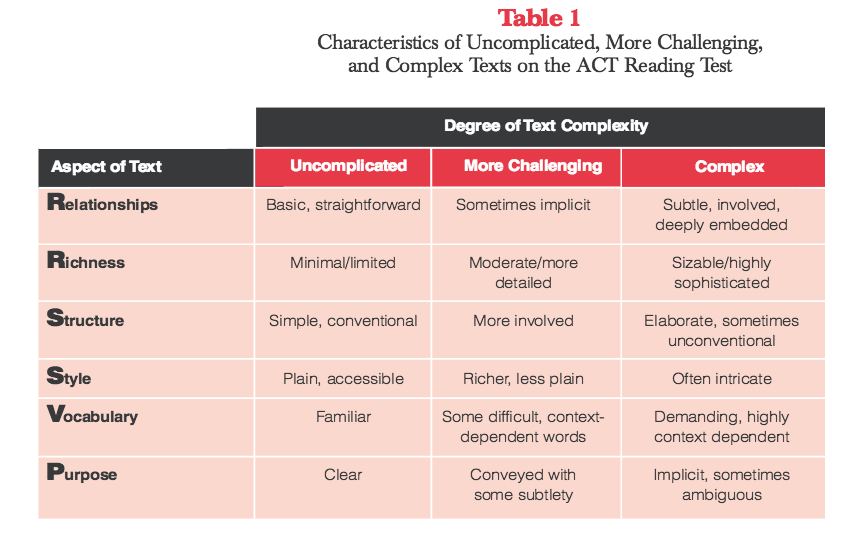

Next, they looked at the focus of the first CCSS-ELA shift, text complexity. Looking at Figure 12 we finally see a significant result. Table 1 shows how they determined the different degrees of text complexity and Figure 12 shows that there is a slight difference between uncomplicated text, where students get more correct answers, and more challenging text, where students get fewer answers correct, but students get much fewer answers correct on complex text until you reach those students who score way higher on the reading ACT. It is a student’s ability to perform well with complex text, according to this ACT study, that determines whether they will be successful after high school and in college! What is refreshing is that the above results were true for students of both genders, all racial/ethnic groups, and all family income levels.

That is why the first shift of the Common Core is to focus on exposing our students to complex texts. In my next post we will look at some of the implications of exposing our students to complex texts for instruction!